52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks

Week 19 | Service

|

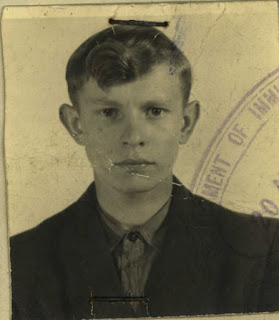

| Frederick McKinlay, circa 1890s |

This week’s theme makes me think of the public service, an

over-arching term used to describe employment in the government sector,

including public schools, and one in which many of my family have worked.

My great-grandfather was the first of our McKinlay family to be

born in Australia and was the first in what has become a long line of teachers

in the family. His entire working life,

starting at age 13 years, was spent in the service of the Queensland Education

Department; a teaching career that spanned over 40 years.

Our teachers have been under an enormous amount of pressure

in recent months, which makes it even more fitting that this week I shine a

light on the amazing work they do, through the story of Frederick McKinlay.

Frederick McKinlay, born 24 July 1879 in Rockhampton, was a

first-generation Australian. His father

John McKinlay was a ship’s engineer from Scotland and his mother Margaret Ann

Stewart a domestic servant from Ireland.

Purportedly, both arrived in Australia on the same ship, the Scottish

Bard, in 1868 (although evidence of John’s arrival has not been found to

date). John and Margaret married in Rockhampton in 1878 (23 September).

The couple moved between Rockhampton and the seaside town of

Emu Park for many years. The first evidence of Fred’s own education is his

admission to Rockhampton Primary School at the age of 8 years and 3 months in

1887. The following year, his father was

working at the Tranganbar Gold Mine where John secured the services of a

retired school master purchased a large tent for use as a makeshift school for

the children at the mine. From there the

family went back to Emu Park, where Margaret ran a boarding house and Fred and

his siblings continued their education at Emu Park School.

In 1893, at the age of 13 years, Fred began his teaching

career, when he was admitted by the Education Department as a pupil teacher at

the Emu Park State School. The pupil-teacher system was essentially an

apprenticeship scheme, with training provided on the job in schools by the head

teacher of the school. Fred trained

under the supervision of Benjamin Long and qualified as a teacher on 31

December 1897.

During the early years of his career, Fred underwent regular

observation by the District Inspector. The

Inspectors’ comments are brief and recorded in cramped hand-writing in Fred’s

teaching record but he is generally described as a fair classroom teacher, who kept

good order in the classroom, was intelligent and industrious and achieved satisfactory

results. Although, one inspector was

less impressed, noting that Fred had fair disciplinary powers of the repressive

order, does work in a vigorous but superficial way, and very unwilling to do

work outside specified school hours. This

last report was by District Inspector Brown who features in another chapter in

the life of Fred in a rather negative way so one wonders whether DI Brown was an

inherently critical man or just had something against Fred. But I digress. Newspaper reports and reminiscences of former

students suggest that he was a successful, valued and kindly teacher with a

genuine appreciation of his students and commitment to their education.

Fred was steadily promoted during the early years of his

career, rising through the various levels to Head Teacher by 1908. Over

the forty years of his career, Fred taught at a dozen schools around Central Queensland and was Head

Teacher at four of these: Emu Park, Georgetown, Rockhampton Central (Boys), Leichardt Ward, Mt Chalmers, Stanwell, Marmor, Brandon, Hamilton Creek, Mt Morgan Boys School, Maryborough Central, and Albert State School (Maryborough).

|

Francia Dow and Frederick McKinlay

Wedding portrait, January 1908 |

When Fred was transferred from Leichardt Ward School to

Mount Chalmers Provisional School at the end of 1907, Head Master Benjamin Long

expressed sorrow that the school was losing Fred, who had been with them almost

since the opening of the school and felt they could not allow him to go without

a small memento of their esteem. Mr.

Long indicated that Fred would be very much missed as he had been a thoroughly

good teacher, a most loyal assistant, and always ready to help in all those

‘hundred and one things’ a teacher had to do out of school. He wished Fred well with the transfer and his

impending marriage to Francia Dow (also a teacher) and hoped the important step

he was taking would lead to the further advancement of his career. He felt that Leichardt Ward’s loss was Mount

Chalmers gain. Fred was presented with

gifts from the teachers and children – a silver teapot and biscuit barrel. Fred expressed his sincere thanks for the

beautiful presents and to Mr. Long for his kind words, attributing ‘most of his

success in life’ to Mr Long, by whom he had been taught both as a student and

as a trainee teacher.

Mt Chalmers was his first posting as a Head Teacher. The prior Head Teacher was his new wife (who

was required to resign from teaching when she married) which must have been an

interesting transition. Fred spent just

one year at Mt Chalmers, but was remembered warmly by one student 75 years

later. Violet Armstrong recalls the day

when she was eight years old and some mineworkers came to the school and took

Fred outside to talk to him. Upon

returning to the classroom, Fred said, “Lillie, Darry and Violet, your mother

wants you at home as there has been an accident at the mine”. He then put on his trademark white helmet,

took the children by the hands and led them out to collect their hats and bags

from where they hung on the veranda. He

accompanied the children on their walk through the scrub and it was only as

they neared their home that he informed them that their father had been

killed. Hearing this news, Violet

recalls that she panicked and fled into the bushland but years later

appreciated the kindness of Mr McKinlay walking her and her siblings home.

Stanwell State School was bounded by a creek, which

regularly flooded in heavy rains, rendering the children unable to cross and

attend school. Rather than have the

children miss school, Fred purchased a boat at his own expense and rowed the

children across the creek each morning and afternoon. Fred’s ferrying services rapidly expanded to

the general public and in representations to the Fitzroy Shire Council for the

construction of a footbridge across the creek, he described having made over 100 trips across the creek

to oblige dairymen, travellers and stockmen, even carrying a cyclist and his

motorcycle on one occasion.

In his roles as Head Teacher, Fred regularly advocated for

improvements to the school facilities for the benefit of teachers and students

alike. While at Stanwell School, another

significant infrastructure problem was that of the latrines, which apparently

filled with water during heavy rains and emitted a ‘most awful stench’. In correspondence to the Department, he

describes having to ‘rush from the ‘office’ with disarranged garments (fortunately

‘twas dark) the stench was so bad. Mrs

McKinlay is quite unable to use the ‘office’ and has to make arrangements

neither convenient nor agreeable’. He also

expressed concern that these conditions were making children ill and cited the genuine

risk of typhoid. At Marmor School, he was successful in efforts to have a new

school building erected and improvements made to the teacher’s residence.

As Head Teacher Fred was also responsible for facilitating

the many extra-curricular activities of these small rural schools. At Stanwell School many successful Arbour Day

events were held, raising money through Sports Days and dances. At Hamilton

Creek school the end of the school year was regularly celebrated with large

picnics. Upon his move south to schools

in the Maryborough District, he was involved with various sporting bodies,

especially in swimming carnivals and as secretary of the combined District

State School Sports Association.

The school buildings in rural schools were regularly used by

community groups such as the Ambulance Brigade and Progress Association for

social and civic activities. This required

Fred to write tedious memos to the Department seeking permission each and every

time a community group requested use of the facilities.

Fred was also active in professional networks and held

several committee roles with the Teachers’ Association (Mount Morgan and

Dawson). A particularly vexed topic was

homework, which Fred asserted was a nuisance for teachers but argued was

invaluable to those children who regularly requested it but did not believe it

needed to be mandatory and advocated for an approach that gave students some

involvement in the choice of task. His

professional activities also involved him supervising pupil teachers.

Fred also had an interest in what we now call ‘adult

education’ or ‘lifelong learning’ and was a member of the public lecture

sub-committee of the Mount Morgan Technical College which organised talks and

lectures on a variety of topics for the broader community.

|

| Hamilton Creek School, circa 1920s |

The longest posting of Fred’s career was to Hamilton Creek

State School, outside Mt. Morgan. This

was when Mt. Morgan was in its heyday and there were numerous state schools

serving the township. It was here that

Fred’s three children grew up and attended school. Fred appreciated a nice garden and the

prolonged period he spent at Hamilton Creek provided an opportunity to see his

plantings established and flourishing.

A rose bush was planted for every child along the lane down to the

road. Tall sprinklers were installed to

spray the garden. A lush quisqualis

rambled on the veranda rails of the teacher’s residence.

During his years in Hamilton Creek Fred purchased a Model T

Ford. A former fellow student of his

daughter Mavis McKinlay, at the age of 103 years, recalled Fred as follows: ‘Oh

yes! McKinlay! He was the school teacher chap. Drove his daughters to school

every day in his Model T Ford’. [See

Week 2’s post for more on this story].

In May 1927, Fred was transferred to the Mt Morgan Boys

School. The locals gathered in the

school on a Saturday night to farewell him.

Mr. F. Toppenberg, an engineer with the Main Roads and President of the

Progress Association, presided and in his remarks eulogised Fred’s qualities,

both as a teacher and as a resident among them.

Fred was presented with a gold pencil and Francia with a silver memento

cup as a token of affection and esteem.

Mr. Campion also spoke of Fred in glowing terms. Fred offered the appropriate responses. The speeches were followed by musical items

(including some performed by Fred’s own daughters), dancing, and supper.

In 1936, Fred took substantial sick leave during July and

August. Unfortunately, in December that year, he was admitted to the Nundah

Private Hospital and passed away on Boxing Day from complications following

emergency surgery for bowel cancer. This

was only three week after the death of his mother.

Fred’s obituary describes him as “very popular with the

scholars”, which is a short statement for forty years of work, but a lovely way

to be remembered.

There was obviously much more to Fred than his role as a

teacher. He was a son, brother, cousin,

husband, father, uncle, grandfather and friend, but that, as they say, is a

story for another day. This week was all

about service and Fred definitely put in many good years with the education

department, starting a tradition of teaching in the family – his brother also

trained as a teacher (although only worked in this profession for a few brief

years), both his daughters trained as teachers, and at least six of his

grandchildren and great-grandchildren are or have been involved in education.

Here’s to Fred and all the wonderful teachers out there,

continuing this tradition of service to education.