52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks

Week 18 | Where there's a will...

This week’s story isn't about an ancestor; rather it’s

about long-term neighbours who feature in our family story. I don’t know all the details of the Slobodians’

family story but their broader narrative leaves no room for doubt that they

faced great sadness, untold horrors and overcame significant challenges in

order to take up farming next door to my Davey family in Eight Mile Plains

(Queensland, Australia).

This is their story as compiled from recollections told to

me by my mother, Irene Davey, and publicly available sources.

|

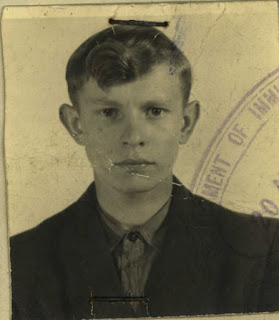

| Zenowij Slobodian, circa 1949 |

On 20 April 1949, former Ukraine national Stanislaw Slobodian

and his three sons, Wolodoymyr, Zenowij, and Omelan stepped off the immigrant ship

Svalbard and onto Station Pier in Melbourne.

It was Omelan’s 19th birthday. This was their first day in Australia. They had boarded the ship a month earlier in

Genoa, Italy, along with 896 other displaced persons, all seeking a new life in Australia following World War II.

At the end of World War II, there was no recognized Ukrainian

state and there were approximately two million Ukrainians amongst the twenty

million ‘foreigners’ who found themselves stranded in Germany when the fighting ceased. All but approximately 200,000 of

the Ukrainians returned either willingly or by force to what was by then the

USSR. The majority of those who remained

in Germany subsisted in approximately 80 (out of a total of 700) displaced

persons camps which were for Ukrainians, awaiting resettlement in countries

such as Australia, the United States, and Canada. The Slobodians had been in Amberg, a camp in US

occupied area of Germany, until the International Refugee Organization arranged

their immigration to Australia.[1]

In exchange for free passage and help on

arrival, they agreed to work for the government for two years.[2]

Frightened by the near invasion of Australia by the

Japanese, Prime Minister Ben Chifley had decreed that Australia must grow its population

as rapidly as possible.[3] In 1949, the Minister for Immigration, Mr A

A Callwell anticipated the year would be “the most vigorous Australian migration year since the gold rushes of the

1850's”.[4] An estimated 25,000 immigrants were expected

to arrive in the month of April alone. Displaced

persons from camps in Europe were expected to make up 11,299 of the immigrants.[5] The Slobodians

were four of this number.

Soon after disembarking the Svalbard in Melbourne, the immigrants

boarded a train for the seven-hour journey to Bonegilla migrant reception camp

in Wodonga on the Victorian/New South Wales border. It was intended that newly

arrived immigrants would spend several weeks in the camp receiving education on

life in Australia and then be dispatched around Australia to industries such as

hydro-electric schemes, cane-cutting, timber-cutting, brick-making and harbour

construction. It wasn’t always this easy,

however, and some stayed months, if not years, in the reception camps. [6]

Although Stanislaw was listed as ‘single’ on the passenger list for the Svalbard, he had been married to Liliana, mother to his sons, but had lost track of her during the turbulent years of the war. Presumably unable to determine her fate or whereabouts, he immigrated without her. Irene recalls that many years later (possibly in the early 1960s), she was located and brought out to Australia. Irene remembers that Liliana couldn’t believe the freedom of Australia. She used to walk down to the catch the bus, saying in wonderment, ‘I go shopping’; amazed that she had money to buy things, that there were things in the shops to buy, and that no-one was stopping her.[7]

Prior to arriving in Eight Mile Plains, Omelan had been working in the forestry somewhere around Kilcoy. In April 1951, he was one of six men injured when a timber truck collided with a utility on the Jimna-Goomeri Road.[8] Omelan suffered compound fractures of both legs and was transported to the Brisbane Hospital.[9] Unfortunately, both legs had to be amputated and he was fitted with artificial legs. However, Irene recalls him dancing and riding a bike with ease.

Omelan subsequently moved to Adelaide where he was heavily involved with the Ukrainian Scouting movement, Plast, and the Ukrainian Philatelic society. He married and had two sons. Omelan died in 2015. In 1966, Irene was working in a fruit canning factory in the Riverina for the summer where she made friends with a girl who was Russian Orthodox. One weekend they travelled to Adelaide to attend church, and Irene was amazed to find Omelan, her one-time neighbour from Eight Mile Plains sitting in the front row.[10]

Zen also worked in Jimna, presumably with the forestry, but later was able to resume his profession as an electrician. His alien registration card indicates that he also went to Adelaide for a short time but subsequently returned to Eight Mile Plains where he built another house on the far back section of the block Stanislaw purchased. Zen married and had three children. He died in 2019.

From Bonegilla, Wolodymyr appears to have gone to Adelaide but also to have lived in Wodonga for a period of time. Wolodymyr married, but how many children he had, if any, is unknown for now.

Today, the Slobodians are recognized with several street namings in Eight Mile Plains – Slobodian Avenue, Lilywood Street (named for the family’s wife and mother), and possibly Stanley Place[11] – and their descendants continue to live in various parts of Australia, some having forged very successful careers.

Along their journey, Stanislaw (and his sons) no doubt asked 'will?' many times: Will we survive the war? Will we see each other again? Will we get out of the displaced persons camp? Will we find a new life? Will we like Australia? Will we fit in? Will we find jobs? Will I walk again? Will I see my wife again? But their story proves that where there's a 'will', there is hope and possibility.

NOTE: I’m far from an expert (in fact, I know barely anything) on Ukrainian history, the fate of Ukrainians during World War II, displaced persons camps or immigrant resettlement, and I haven’t met any Slobodian family members (yet). There is much more to the story of this family than is contained here (although my wish is that I might have an opportunity to learn more one day). In piecing together this brief account of our neighbours of twenty-plus years, the Slobodians, I hope I have not only acknowledged their part in our family's story, but have respectfully paid tribute to their part in Australia’s story.

[1]

Summary drawn from information contained in the notes from a lecture presented

by Professor Orest Subtelny, Friday March 7, 2003 at the Ukrainian Museum in New York

City, http://www.brama.com/news/press/030311subtelny_DPcamps.html

[3]

Ibid

[4]

‘Great Migrant Armada’, The Scone Advocate, 1 April 1949, p. 7

[5]

Migration in Australia, op cit

[6]

Migration in Australia, op cit

[7]

Pers comm., Irene Davey, April 2020

[8]

‘6 Injured in Collision’, Brisbane Telegraph, 7 April 1951, p. 4

[9]

Ibid.

[10]

Pers. Comm., Irene Davey, April 2020

[11]

Stanislaw later went by the name Stanley

Thank you for telling our story. Irene Peter nee Slobodian

ReplyDeleteThank you Irene. Lovely to connect with a family member. I'd love to chat more if you were interested. You could contact me via the links in my profile. The Janeologist

ReplyDeleteI enjoyed reading this very much. My first husband was Bohdan Slobodian, the son of Wolodymyr Slobodian and I am researching the Slobodian line for my sons.

ReplyDeleteThank you Annette. I'm so pleased you found the story and to have heard from another family member. If you'd like to chat some more or if I can assist you with your research, please contact me via the links in my profile.

Delete